The Trouble With (an) Old Space Opera

Apr. 14th, 2019 07:58 pmI don't remember for sure when I first realized that stories were written by actual people, by writers. Probably, it was a gradual process that led to my understanding that stories didn't just exist, like lakes or forests or mountains, but that they were made.

I do remember when I realized that television shows were also written by actual people. That came about when I found a paperback book, one that featured a colour photo of William Shatner as Captain James T. Kirk, wearing a harassed expression while up to his shoulders in tiny furry animals that us cognoscenti knew as tribbles.

That paperback carried the name of my favourite episode of Star Trek: The Trouble With Tribbles. The author was called David Gerrold, and the book was a memoir of sorts, the story of how Gerrold came to write the episode and what he learned during its production.

At the time — I'm going to guess it was 1974 or 1975, which would have made me nine or ten years old — I thought it was both a bravely honest and an insightful book, and it's been so long since then that I won't argue with my younger self. Certainly it was interesting enough the I happily found the wherewithal to purchase his follow-up, The World of Star Trek, and both books have a warm, if by now pretty vague place in my long-term memory.

What strikes me as strange, is that — though I read a few of his short stories because they were in an anthology or magazine I'd purchased anyway — I never sought out any of Gerrold's fiction. Considering that "The Trouble with Tribbles" still holds up as good television writing, and that it was an episode I'd loved as a kid, I can't really explain why I didn't, unless it was a bit of subconscious snobbery that saw television as a lesser order of literature than prose.

(If so, maybe I was actually displaying pretty good critical judgement; even the best television drama of those days — and well into the 21st century — was simply too formulaic to rival the best of literature. But I digress.)

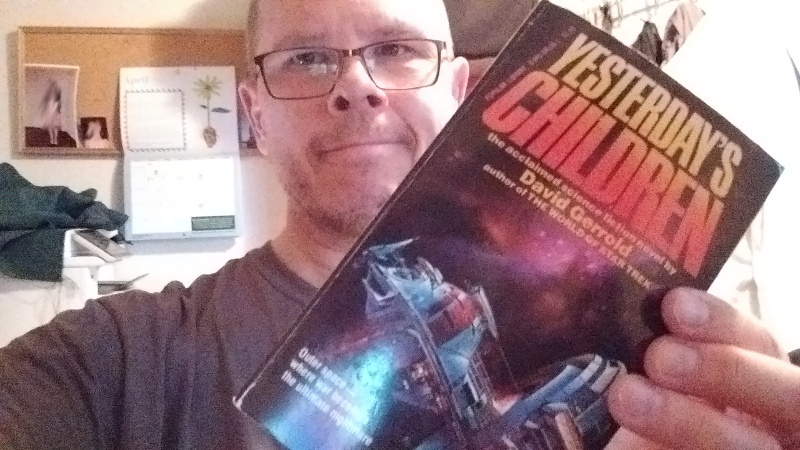

In any case, a chance finding of an almost 40-year paperback has finally seen me sample Gerrold's fiction, a novel that nevertheless had its initial origin as a rejected proposal for an episode of Star Trek, a novel first published in 1972, then revised for a second lease on life in 1980.

And what an oddly dated novel it is.

I am sick of reviews that are almost entirely synopses, so I won't be providing you with one here. Suffice it to say that Yesterday's Children (now titled Star Hunt) is set in a far future remarkably similar to the Trek universe. Earth is the centre of a interstellar federation of sorts, called the United Systems. The US is involved in a long-running war that, if it is not losing, is certainly taking its toll, including maintaining as operational starships which are overdue for decommissioning.

Enter the USS Roger Burlingame, a decrepit warship with a demoralized, poorly-trained crew and a captain who spends most of his time in his cabin, leaving the day-to-day operations to First Officer Jon Korrie, an ambitious man who longs for combat and the glory of a successful kill.

An enemy ship is spotted, the Roger Burlingame gives chase and the game is on.

Yesterday's Children is a tightly-plotted story: a cat-and-mouse piece of military SF and a psychological mystery, as it gradually becomes clear that the enemy being chased might, or might not, be real. Until the very end, Gerrold keeps the reader wondering whether they are reading a straight-forward war story or a riff on The Caine Mutiny.

And on both those levels, it is a story pretty well-told.

But I said it is also a very dated novel, and it is. In the first place, the narrative voice and the psychological aspects echo not the 1970s, when the novel was written, but the 1940s and 1950s. With the elision of the very occasional "fuck", it would not have seemed out-of-place as a serial published in John W. Campbell's Astounding.

Jon Korrie is, or believes he is, a mentally superior human, an adept of something called psychonometrics, a hand-wavium which permits him to manipulate his crew (or to believe he is manipulating his crew) with cold calculations that can be brutal. Suffice it to say that I found psychonometrics about as plausible as Asimov's psychohistory: a conceit I could accept for the sake of the story, but not one I could believe was actually possible.

What is even more dated about Yesterday's Children (and something that I suspect would make it simply unreadable for a lot of readers under, say, 35) is that it includes not a single female character.

Granted that first world militaries of the 1970s were pretty much all-male, especially on-board the real-world equivalent of starships, but Gerrold cut his writer's teeth on Star Trek, so the idea that women might belong onboard a starship wasn't exactly unheard of in 1972, nevermind 1980, when then book was re-published in an updated edition. In 2019, it seems merely bizarre to read a novel in which women are simply absent.

Despite that absence, I enjoyed Yesterday's Children well enough. I wanted to find out what would happen next and whether or not Korrie was sane, but it's not a story that will stay with me over the long term. Even a week after I finished it, the details are fading fast.